Time:2025-12-09 Views:1 source:News

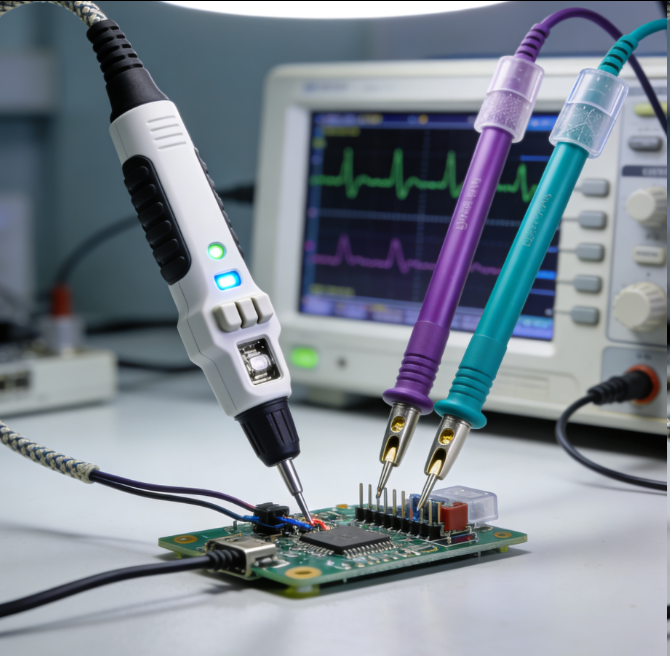

Instrument probes are high-precision, application-specific tools designed to interface with scientific, industrial, or engineering instruments—such as oscilloscopes, signal analyzers, spectrum analyzers, or precision multimeters—to measure, capture, and transmit electrical, electronic, or physical signals. Unlike general-purpose electric meter probes (which handle basic voltage/current measurements), instrument probes are engineered for specialized tasks that demand extreme accuracy, high bandwidth, low noise, or compatibility with unique signal types (e.g., high-frequency RF signals, low-level sensor signals, or high-voltage industrial signals). They are used in fields like electronics engineering (testing circuit board designs), telecommunications (analyzing RF signals), aerospace (monitoring aircraft systems), and medical device development (measuring biosignals). The core purpose of instrument probes is to preserve the integrity of the original signal during measurement—ensuring the instrument receives an accurate representation of the signal, free from distortion, noise, or interference.

Key technical features that define instrument probes and their specialization include:

High bandwidth and signal fidelity: For instruments that analyze fast-changing signals (e.g., oscilloscopes used to test microchip circuits), probes must have a wide bandwidth (the range of frequencies they can transmit without attenuation). Bandwidth ratings typically range from 100MHz (for general-purpose probes) to 10GHz+ (for high-frequency RF probes). To maintain signal fidelity, these probes use low-capacitance designs (e.g., 10pF-20pF for oscilloscope probes) and matched impedance (50Ω or 75Ω) to prevent signal reflection—critical for high-frequency signals (above 100MHz), which are sensitive to impedance mismatches. For example, a 1GHz bandwidth probe paired with an oscilloscope can accurately capture the waveform of a microprocessor’s clock signal (which operates at hundreds of MHz), allowing engineers to verify timing and stability.

Low noise and high sensitivity: In applications where signals are weak (e.g., measuring sensor outputs in medical devices or industrial sensors), instrument probes must have low inherent noise and high sensitivity. Low-noise probes use shielded cables (with multiple layers of metal shielding) to block external electromagnetic interference (EMI) and conductive materials with low thermal noise (e.g., gold-plated conductors) to reduce internal noise. Some probes include built-in signal amplifiers (with gain levels of 10x-100x) to boost weak signals (e.g., 1mV-10mV) to levels that the instrument can detect accurately. For example, a low-noise probe used in biomedical engineering can measure the tiny electrical signals from a heart rate sensor (microvolt range) without adding noise that would distort the data.

Specialized designs for unique signals: Instrument probes are tailored to specific signal types and environments:

RF probes: Used with spectrum analyzers to measure radio frequency signals (e.g., in telecommunications or Wi-Fi devices). They have coaxial connectors (SMA or N-type) for impedance matching and are designed to minimize signal loss at high frequencies (up to 6GHz or higher).

High-voltage probes: For measuring voltages above 1000V (e.g., in power distribution systems or industrial equipment), these probes include voltage dividers (resistive or capacitive) to scale down high voltages to levels the instrument can handle (e.g., 1000V to 1V). They have thick insulation and safety shields to protect users from electric shock.

Current probes: Instead of measuring voltage, these probes detect electric current by measuring the magnetic field around a wire (using a Hall effect sensor or current transformer). They are non-invasive (no need to break the circuit) and are used to measure AC or DC current in power systems, motors, or electronic devices.

Temperature probes: While not purely electrical, these probes (used with data loggers or thermometers) convert temperature into an electrical signal (e.g., resistance change in a thermistor) and are classified as instrument probes due to their precision (±0.1°C for laboratory use).

Calibration and accuracy: Instrument probes require regular calibration to maintain accuracy—most manufacturers provide calibration certificates and recommend annual recalibration (or more frequently for high-precision applications). Calibration ensures that the probe’s measurements match a known standard (e.g., a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) traceable standard). For example, a precision voltage probe may have an accuracy of ±1% of the measured value when calibrated, ensuring reliable results in critical applications like aerospace component testing.

Practical applications of instrument probes:

Electronics design and testing: Engineers use oscilloscope probes to test printed circuit boards (PCBs)—measuring the voltage waveform of a microchip’s data lines to check for signal integrity (e.g., bounce or skew). RF probes test wireless devices (e.g., smartphones) to ensure they transmit signals within regulatory frequency bands (e.g., 2.4GHz for Wi-Fi).

Industrial automation: Current probes monitor the current draw of factory motors—an unexpected increase in current indicates a mechanical fault (e.g., a jammed bearing), allowing maintenance teams to intervene before the motor fails. High-voltage probes test power inverters in solar energy systems to verify they convert DC power to AC power efficiently.

Medical device development: Low-noise probes measure biosignals like EEG (brain waves) or ECG (heart signals) in medical devices—ensuring the device captures accurate data for diagnosis or monitoring. Temperature probes monitor the temperature of medical equipment (e.g., MRI machines) to prevent overheating.

Aerospace and defense: High-reliability probes test aircraft electrical systems (e.g., avionics) to ensure they operate safely at extreme temperatures (-55°C to 125°C) and under vibration. RF probes test radar systems to verify their range and signal clarity.

When selecting an instrument probe, match its specifications to the application: bandwidth (for high-frequency signals), sensitivity (for weak signals), voltage/current rating (for high-power circuits), and environmental resistance (for harsh conditions). With their precision and specialization, instrument probes are essential for advancing technology and ensuring the reliability of critical systems across industries.

Read recommendations:

Magnetic Pogo Pin Connector quotation